by Evelyn Gan and Ellysha Cheng

When we were living in Kupang, West Timor, my husband Timothy was sent to an island not too far away. He attended a church service there where everything was in Bahasa Indonesia. The congregation sang all the hymns with gusto and could recite the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostle’s Creed. They knew the liturgy so well; they knew what to say and when they should be saying it. However, when it came to the announcements, it was all in Helong, their heart language.

This was because all information for their village, including from the government, would be told to the people during this time. They wanted to make sure that everyone understood and did not miss out on anything because most adults did not know Bahasa Indonesia well.

It is quite amazing that the Helong people could sit through sermons, sing along to songs, and perfectly recite the liturgy – all in a language they did not know. They actually received the printed New Testament in their language not too long ago. Thinking of how well they learn from listening, I hope they will have an audio version of it too. However, I can’t help but think an oral Bible translation would speak to their hearts more directly.

Oral Bible Translation done well is like listening to an engaging speaker who knows what he or she is talking about, using a language that is easy to understand. Because the speaker knows their topic or story well, they would not go in circles but instead speak clearly and directly.

Now, what is the difference between an audio Bible and an Orally translated Bible?

An audio Bible is a recording of a written Bible being read. An oral Bible is when the whole process of translating the Bible is done orally.

Let’s put it another way:

An audio Bible is a recording of a written Bible that is meant to be read.

An oral Bible is a recorded Bible that is meant to be listened to.

But aren’t they the same? They are actually, because both are the Word of God.

A well translated oral Bible is like a well translated written Bible because it is accurate and faithful to the original text. Like written translations of the Bible, an oral translation is exegeted, checked by the exegete, then by team members, then by the community (sometimes more than once), and then a consultant. Finally, it is reviewed by pastors or church leaders.

You might be wondering, ‘Then, why do oral translation? Why not just do a written translation, have someone read it, and record the reading?’

Well, when we speak, we arrange our words differently than when we write, which makes it is easier for others to comprehend and digest the message that they hear.

The most important component of Oral Bible Translation is the internalisation process. As you cannot translate what you do not know or understand, this process requires translators to learn the who, what, why, when, where, and how in order to grasp the passage, situation, storyline, implied meaning, and big picture.

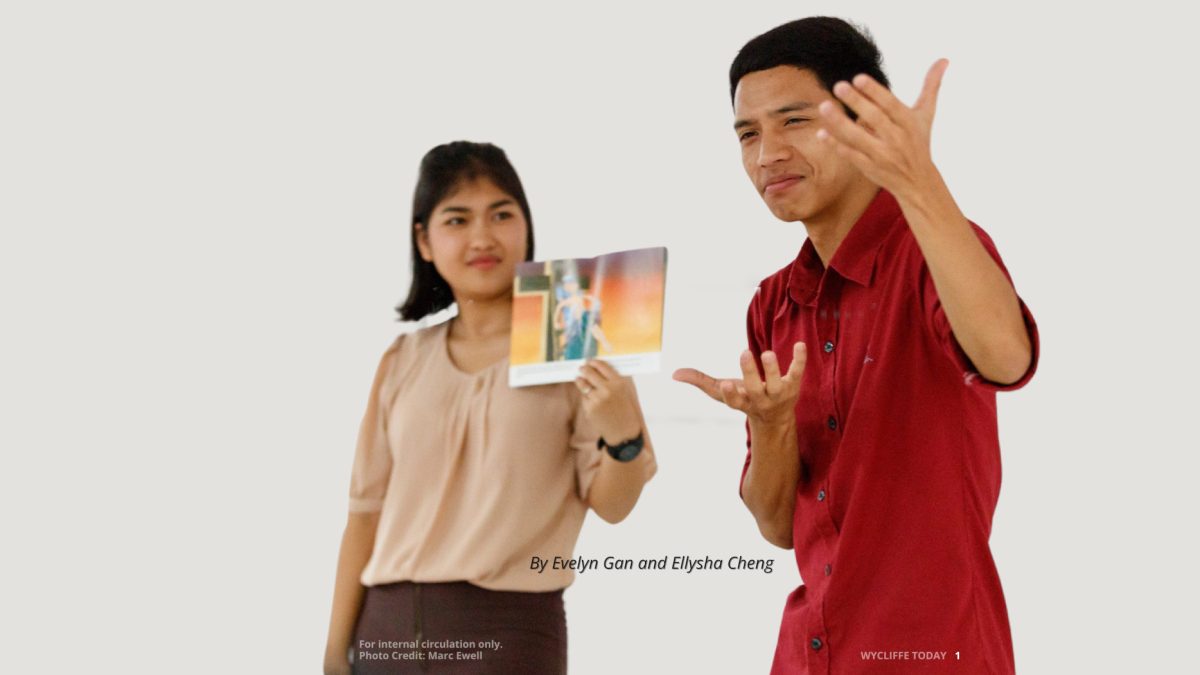

They process all these information by talking and asking questions, by acting and drawing it out, by using props to show and tell. They know the passage so well that they can tell it as if they are part of the passage, because the passage has become part of them.

Romania. Photo credit: Heather Pubol

Like story tellers, they then craft the message in their own language so that listeners can understand it well. They tell those passages with the right emotion, intonation, and volume, all at the right places. Their team members make sure they do not deviate from the original meaning, and their translation advisor double or triple checks the translation.

After this, they get people from their communities to listen and take care that people understand, so that nothing could be misunderstood. In communities that have believers, they have pastors and church leaders to listen and ensure that the translation is accepted by the church. In many translation projects, the passages are also checked by translation consultants, who approve the passages for publishing. Finally, the passages are recorded and shared out.

There are so many communities like the Helong around the world, and while many of these communities today have become literate, they may still have a preference for listening. They learn better and faster using their ears than reading from a printed book.

I had never seen myself as an oral learner. Growing up, my parents made sure we knew our ABCs, learnt to read, and went to school. Our school learning has always been literacy based.

However, if we think again, our earliest learning is oral. Mothers sing to their babies and teach them nursery rhymes. Many of us have learnt the Lord’s Prayer because we had heard them over and over again. We have learnt many songs not by reading the lyrics but by listening to them many times. We know stories, fables, and sayings because we have heard them from our grandparents, parents, siblings, and friends. We learn these things orally without much effort because these are done communally.

Oral Bible translation is not something new. Traditionally, when missionaries translated the Bible with their mother tongue speakers who did not know how to read, they would teach and share the passages. Then, the mother tongue speakers would tell them how they would say the passages in their language, and the missionaries would write them down.

Today, Oral Bible translation is for everyone, but especially for those who prefer listening to reading, whose eyes no longer see so easily, who do not read, or who process information more easily through listening.

Those who have ears, let them hear!